U

Uterus

Hollow muscular organ for fetal development

RegionPelvis and Perineum

SystemReproductive System

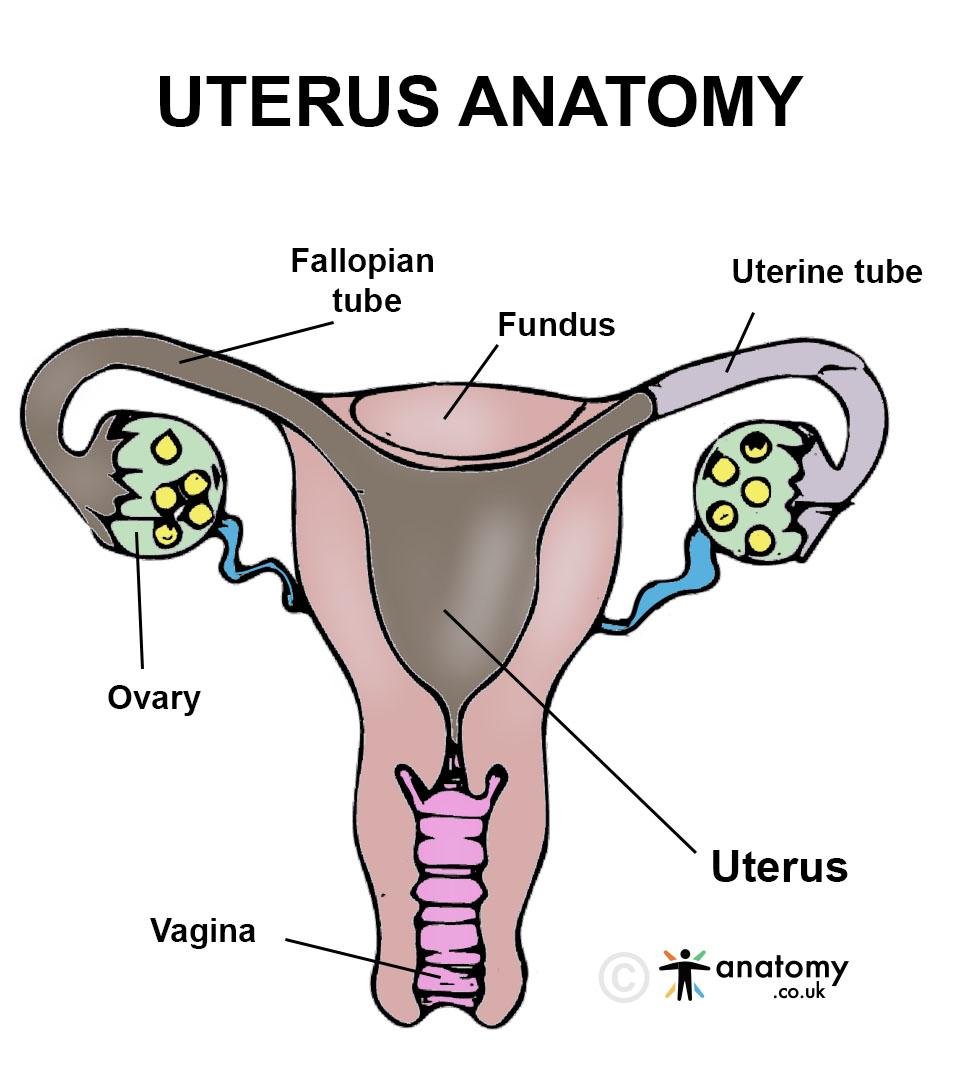

The uterus is a hollow, muscular organ located in the female pelvic cavity, positioned between the bladder and the rectum. It is pear-shaped and consists of three main parts: the fundus (upper rounded portion), the body (main central part), and the cervix (lower, narrow portion that opens into the vagina). The uterus is connected to the fallopian tubes at the upper part (uterine horns) and is anchored in the pelvis by several ligaments, including the round ligaments, uterosacral ligaments, and cardinal ligaments. Its central position in the pelvis plays a crucial role in the reproductive system.

Anatomy

The uterus is a key reproductive organ in the female body, with a complex structure that allows it to support pregnancy and menstruation. Its anatomy includes several distinct parts, each with unique structural features. Below is a detailed description of the anatomy of the uterus.

Location and Position

The uterus is located in the pelvic cavity, positioned between the bladder and the rectum.- Anterior Relation: The uterus is situated posterior to the bladder and anterior to the rectum. The space between the uterus and the bladder is known as the vesicouterine pouch.

- Posterior Relation: The rectum lies posterior to the uterus, separated by the rectouterine pouch (also known as the pouch of Douglas), a small space between the rectum and uterus.

- Position in the Pelvis: In most women, the uterus is in an anteverted position, meaning it tilts forward, resting on the bladder. It can also be in an anteflexed position, where the body of the uterus is bent forward over the cervix.

External Anatomy

The uterus is pear-shaped and consists of three main anatomical parts: the fundus, the body, and the cervix.- Fundus: The fundus is the upper, dome-shaped portion of the uterus, located above the openings of the fallopian tubes. It is the broadest part of the uterus and is important in pregnancy, as this is where the fertilized egg implants and develops.

- Body (Corpus): The body, or corpus, is the central portion of the uterus and makes up the bulk of the organ. It is lined by the endometrium (inner mucous membrane) and surrounded by a thick layer of smooth muscle called the myometrium. The body tapers as it extends downward to connect with the cervix.

- Cervix: The cervix is the narrow, lower part of the uterus that connects the uterine cavity to the vagina. It acts as a gateway between the uterus and the vaginal canal. The cervix has two parts:

- Internal Os: The opening between the uterus and the cervix.

- External Os: The opening between the cervix and the vagina.

Layers of the Uterus

The wall of the uterus is composed of three distinct layers, each with a specific structure and function.- Endometrium: This is the innermost lining of the uterus, consisting of glandular epithelium. The endometrium undergoes cyclical changes during the menstrual cycle, thickening in preparation for implantation and shedding during menstruation if fertilization does not occur. It consists of two layers:

- Functional Layer: The outer layer that thickens and is shed during menstruation.

- Basal Layer: The inner layer that remains after menstruation and regenerates the functional layer.

- Myometrium: The myometrium is the middle, thickest layer of the uterus and consists of smooth muscle.[7] It is responsible for the strong contractions of the uterus during labor. The myometrium is made up of three layers of smooth muscle fibers that run in different directions (longitudinal, circular, and oblique), allowing the uterus to contract forcefully.

- Perimetrium: The perimetrium is the outermost layer of the uterus, made up of a thin layer of serous membrane. It is continuous with the visceral peritoneum, which covers the pelvic organs. This layer helps protect the uterus and provides a smooth surface for the uterus to move within the pelvis.

Blood Supply

The uterus has a rich blood supply, mainly from branches of the internal iliac artery.- Arterial Supply: The primary source of blood to the uterus is the uterine artery, which arises from the internal iliac artery. The uterine artery branches into smaller vessels that penetrate the myometrium and endometrium. The uterus also receives blood from branches of the ovarian artery and the vaginal artery, providing additional vascular support.

- Venous Drainage: Venous blood from the uterus drains into the uterine venous plexus, which ultimately drains into the internal iliac vein. This network of veins is important for removing deoxygenated blood and waste products from the uterus.

Lymphatic Drainage

The lymphatic system plays an important role in draining lymph from the uterus and protecting the body from infections or diseases.- Upper Uterus: Lymph from the upper part of the uterus drains into the lumbar (para-aortic) lymph nodes, which are located near the lower back and receive lymph from the ovaries as well.

- Lower Uterus and Cervix: Lymph from the lower uterus and cervix drains into the internal iliac and external iliac lymph nodes, which are located along the pelvic walls. Additional drainage occurs through the sacral lymph nodes, which are situated near the sacrum.

Nerve Supply

The uterus is innervated by both autonomic and sensory nerves, allowing for involuntary functions such as uterine contractions and pain sensations.- Autonomic Nerve Supply: The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary uterine contractions. The sympathetic fibers arise from the inferior hypogastric plexus, while the parasympathetic fibers come from the pelvic splanchnic nerves. These nerves regulate the contraction of the myometrium during menstruation and labor.

- Sensory Nerve Supply: Sensory innervation of the uterus is primarily provided by the T11-L2 spinal nerves, which carry pain signals during menstruation and labor. These nerves transmit sensory input to the central nervous system, resulting in sensations of uterine pain or cramping.

Ligaments Supporting the Uterus

Several ligaments support the uterus, anchoring it within the pelvic cavity and maintaining its position.- Broad Ligament: A double-layered fold of peritoneum that extends from the sides of the uterus to the lateral pelvic walls. It helps support the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries and forms the mesometrium, mesovarium, and mesosalpinx.

- Round Ligaments: These ligaments extend from the uterine horns, pass through the inguinal canal, and terminate in the labia majora. They help maintain the anteverted position of the uterus.

- Uterosacral Ligaments: These ligaments connect the cervix and upper part of the vagina to the sacrum, providing posterior support to the uterus and helping prevent prolapse.

- Cardinal Ligaments: Also known as the transverse cervical ligaments, these ligaments extend from the cervix to the lateral pelvic walls and provide lateral support to the uterus and cervix.[8]

Fallopian Tube Connection

The uterus is connected to the fallopian tubes, which extend from the upper lateral parts of the uterus (the uterine horns) and serve as conduits for eggs traveling from the ovaries to the uterus.- Uterine Horns: These are the regions where the fallopian tubes enter the uterus. The horns mark the transition between the uterus and the fallopian tubes and serve as important anatomical landmarks.

- Fallopian Tubes: The fallopian tubes carry eggs from the ovaries to the uterine cavity, where fertilization may occur. Each tube is approximately 10-12 cm long and consists of four parts: the infundibulum, ampulla, isthmus, and intramural portion (part that connects to the uterus).

Histological Features

The histological structure of the uterus is specialized for its reproductive functions, particularly in pregnancy and menstruation.- Endometrium: The endometrium contains glandular and epithelial cells, which undergo cyclical changes in response to hormones.[6] The glands secrete substances that support potential embryo implantation and pregnancy.

- Myometrium: The myometrium consists of bundles of smooth muscle fibers, which contract during labor and menstruation. It also contains connective tissue and blood vessels to support the uterine structure.

- Perimetrium: The perimetrium is a thin, protective serous membrane that covers the outer surface of the uterus. It is continuous with the peritoneum of the pelvic cavity, forming a smooth interface between the uterus and surrounding organs.

Function

The uterus plays an essential role in reproduction, menstruation, and pregnancy. Its structural design allows it to perform multiple functions critical for maintaining the reproductive health of women. Below is a detailed explanation of the uterus's primary functions.Site for Menstruation

The uterus plays a central role in the menstrual cycle, which prepares the body for pregnancy each month.- Endometrial Shedding: During each menstrual cycle, the inner lining of the uterus, known as the endometrium, thickens in preparation for the potential implantation of a fertilized egg. If fertilization does not occur, the functional layer of the endometrium is shed during menstruation, resulting in the monthly menstrual flow. This process is essential for the renewal of the endometrial lining, preparing the uterus for a future pregnancy.[5]

- Hormonal Regulation: The uterus responds to hormones like estrogen and progesterone, which regulate the thickening and shedding of the endometrial lining. These hormones, produced by the ovaries, trigger the menstrual cycle and guide the uterus through the phases of preparation and shedding.

Site for Fertilization and Early Embryonic Development

The uterus plays a significant role in early embryonic development if fertilization occurs.- Implantation: After fertilization, the zygote travels down the fallopian tube and into the uterus. The endometrium provides a nourishing environment for the implantation of the fertilized egg (blastocyst). Once the blastocyst reaches the uterus, it embeds itself into the thickened endometrial lining, where it begins to grow and develop into an embryo.

- Support for Early Development: The endometrial glands secrete nutrients that support the early development of the embryo.[4] These nutrients are critical for sustaining the embryo before the placenta fully forms and takes over the task of supplying oxygen and nutrients.

Support and Nourishment of Pregnancy

One of the primary functions of the uterus is to support and nourish the fetus during pregnancy.- Formation of the Placenta: After implantation, the uterus plays a key role in the formation of the placenta, an organ that attaches the fetus to the uterine wall. The placenta acts as the lifeline between the mother and fetus, facilitating the exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products between the mother’s bloodstream and the developing fetus. The uterus helps house and sustain the placenta throughout pregnancy.

- Protection of the Fetus: The muscular walls of the uterus, particularly the myometrium, expand as the fetus grows, creating a protective environment that shields the fetus from external pressures or trauma. The uterus also produces amniotic fluid, which fills the amniotic sac and cushions the fetus, allowing it to move freely within the uterus during development.

- Adaptation to Fetal Growth: The uterus expands significantly during pregnancy to accommodate the growing fetus. The myometrium provides the strength and elasticity needed for this expansion, allowing the uterus to stretch while maintaining its ability to contract effectively when necessary.

Contraction During Labor

The uterus plays a central role in labor and childbirth, delivering the baby through the vaginal canal.- Uterine Contractions: During labor, the myometrium contracts rhythmically to help push the baby out of the uterus and through the birth canal.[3] These contractions are initiated by the release of oxytocin, a hormone produced by the hypothalamus. The contractions help dilate the cervix, allowing the baby to move down into the vaginal canal.

- Expulsion of the Placenta: After the baby is delivered, the uterus continues to contract to facilitate the expulsion of the placenta. This process is crucial for preventing excessive bleeding by allowing the uterus to return to its smaller, pre-pregnancy size and compressing the blood vessels at the placental site.

Postpartum Recovery

After childbirth, the uterus plays a role in the recovery of the reproductive system by helping the body return to its pre-pregnancy state.- Uterine Involution: Following childbirth, the uterus undergoes involution, a process by which it returns to its normal size and shape. The myometrial contractions that occur in the days after delivery help shrink the uterus by expelling any remaining blood, tissue, and fluid. This process is crucial for preventing postpartum complications like hemorrhaging and ensuring the uterus is ready for future pregnancies.

- Restoration of the Endometrium: During the postpartum period, the endometrium regenerates after shedding the tissue associated with pregnancy and childbirth. The basal layer of the endometrium helps rebuild the functional layer, allowing the uterus to regain its menstrual and reproductive functions.

Hormonal Regulation and Feedback

The uterus plays an indirect role in the regulation of hormones related to reproduction.- Estrogen and Progesterone Response: The uterus is highly responsive to the ovarian hormones estrogen and progesterone, which control its growth, blood supply, and preparation for pregnancy. These hormones regulate the menstrual cycle, influencing the thickness of the endometrium and preparing it for possible implantation.

- Hormonal Feedback to the Ovaries: The uterus also participates in feedback mechanisms that regulate the reproductive system.[2] During pregnancy, the uterus, in conjunction with the placenta, produces hormones like human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which signals the ovaries to halt ovulation and maintain the pregnancy. Hormonal feedback loops ensure proper communication between the ovaries, uterus, and other reproductive organs.

Support of Other Pelvic Organs

The uterus plays an important role in maintaining the structural integrity of the pelvic cavity by providing support to other pelvic organs.- Supporting the Bladder and Rectum: The uterus, particularly through its ligamentous attachments, helps support the bladder and rectum. The uterus is positioned between these organs, and its proper anatomical position ensures that the bladder and rectum maintain their correct locations within the pelvis.

- Prevention of Organ Prolapse: The broad ligament, round ligament, uterosacral ligaments, and cardinal ligaments anchor the uterus within the pelvis, providing support to the surrounding pelvic structures. A properly supported uterus helps prevent conditions like bladder prolapse (cystocele) or rectal prolapse, where these organs descend into the vaginal canal due to weakened pelvic support.

Uterine Sensory Function

Although the uterus is mainly involved in reproduction, it also has a sensory function, particularly related to pain.- Menstrual Cramps (Dysmenorrhea): The uterus is involved in the sensation of menstrual cramps, caused by the contraction of the myometrium during menstruation. These contractions help expel the endometrial lining but can cause pain due to the release of prostaglandins, which trigger uterine contractions and stimulate pain receptors.[1]

- Labor Pain: During labor, the uterus generates pain signals as the cervix dilates and the myometrial contractions intensify. These pain signals are transmitted to the brain via the T11-L2 spinal nerves and are a key part of the labor experience.

Clinical Significance

The uterus plays a central role in female reproductive health, and its clinical significance is vast. Conditions affecting the uterus can impact menstruation, fertility, pregnancy, and overall pelvic health. Common uterine disorders include fibroids(benign growths), endometriosis (where uterine tissue grows outside the uterus), and uterine prolapse (where the uterus descends into the vaginal canal due to weakened pelvic support). Additionally, uterine cancer and cervical cancer are critical concerns that require regular screening, such as Pap smears, to detect abnormalities early. The uterus is also central to fertility and pregnancy. Conditions like uterine malformations, scarring (from infections or surgery), or adenomyosis can impact a woman’s ability to conceive or maintain a pregnancy. Uterine health is closely monitored during pregnancy to ensure proper fetal development and to detect conditions such as placenta previa or preterm labor. Surgically, the uterus is involved in procedures like hysterectomy (removal of the uterus), commonly performed for severe fibroids, cancer, or uncontrolled bleeding. Maintaining or restoring uterine health is critical for reproductive success and overall pelvic stability.Published on November 30, 2024

Last updated on May 19, 2025

Last updated on May 19, 2025