SI

Small intestine

Main organ for nutrient absorption

RegionAbdomen

SystemDigestive System

The small intestine is a long, coiled tubular organ in the digestive system that connects the stomach to the large intestine. It is the primary site for digestion and absorption of nutrients. The small intestine is divided into three segments: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, each specialized for different aspects of digestion and nutrient uptake. Its inner surface is highly folded with villi and microvilli, increasing the surface area for efficient absorption.

Location

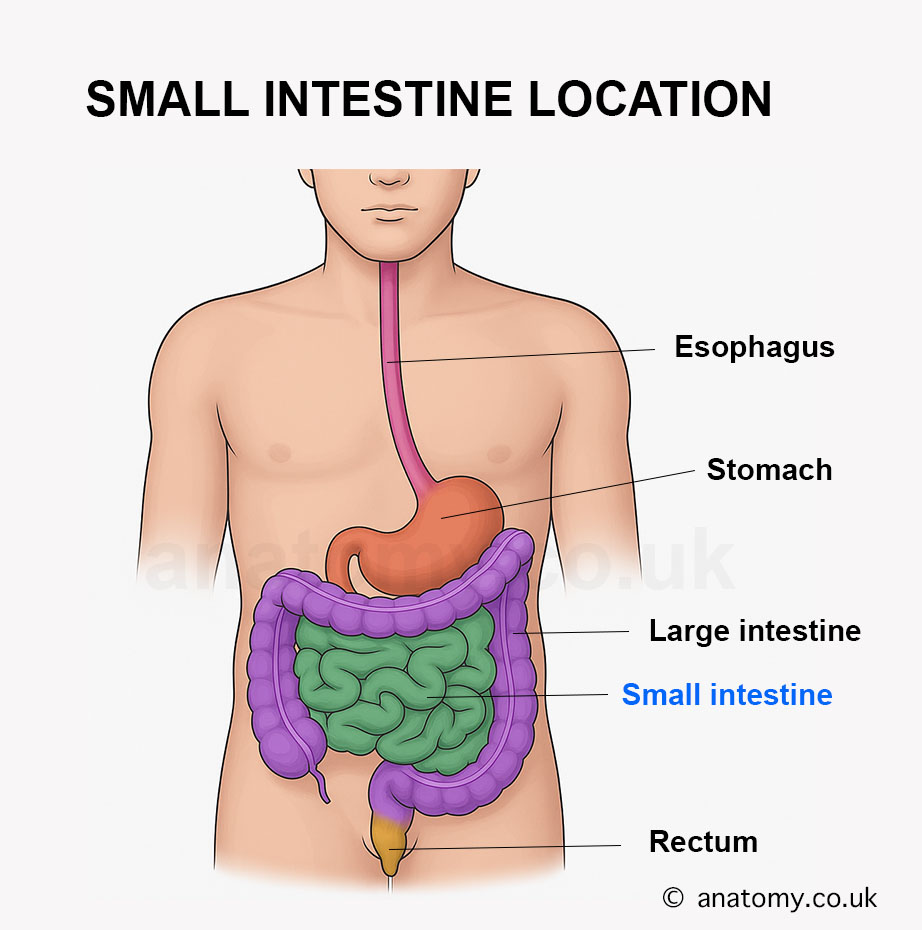

The small intestine is located in the central and lower abdomen. It begins at the pyloric sphincter of the stomach and ends at the ileocecal valve, where it joins the large intestine. It occupies most of the abdominal cavity, surrounded by the large intestine.

Anatomy

The small intestine is a tubular organ that is the longest part of the digestive system. It is highly specialized for digestion and nutrient absorption, with unique structural and anatomical features. Below is a detailed description of its anatomy:

Segments of the Small Intestine

The small intestine is divided into three sections, each with distinct characteristics: Duodenum:

The first section, approximately 25 cm (10 inches) long, is C-shaped.

It is primarily retroperitoneal, except for the proximal part.

Divided into four parts:

Superior (First) Part: Begins at the pylorus, connected to the stomach.

Descending (Second) Part: Contains the major duodenal papilla, where bile and pancreatic ducts open.

Horizontal (Third) Part: Crosses anterior to the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava.

Ascending (Fourth) Part: Ends at the duodenojejunal flexure, supported by the ligament of Treitz.

The middle section, about 2.5 meters (8 feet) long.

It is intraperitoneal and suspended by the mesentery, making it mobile.

Located in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen.

Characterized by prominent plicae circulares (circular folds) and a thicker wall.

The final section, about 3.5 meters (12 feet) long.

It is intraperitoneal and ends at the ileocecal valve, where it connects to the cecum of the large intestine.

Located in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen.

Has fewer plicae circulares and more Peyer’s patches (lymphoid tissue).

Length and Diameter

Total length: Approximately 6-7 meters (20-23 feet).

Diameter: Ranges from 2.5-3 cm in the duodenum and jejunum to slightly narrower in the ileum.

Wall Structure

The wall of the small intestine consists of four layers:

The innermost layer, lined with simple columnar epithelium and goblet cells.

Features:

Villi: Finger-like projections that increase surface area for absorption.

Crypts of Lieberkühn: Glands at the base of the villi that secrete digestive enzymes and new epithelial cells.

Microvilli: Microscopic projections on the epithelial cells forming the brush border, further increasing surface area.

Peyer’s Patches: Aggregates of lymphoid tissue, primarily in the ileum.

Contains connective tissue, blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves.

In the duodenum, Brunner’s glands secrete alkaline mucus to protect against stomach acid.[7]

Muscularis Externa:

Composed of two layers of smooth muscle:

Inner circular layer: Facilitates segmentation and mixing.

Outer longitudinal layer: Responsible for peristalsis.

Coordinated movements push chyme through the intestine.

Serosa/Adventitia: Most of the small intestine is covered by serosa (visceral peritoneum), except for the retroperitoneal duodenum, which is covered by adventitia.

Vascular Supply

Arterial Supply:

Primarily supplied by the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), which gives off branches to the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

The proximal duodenum is also supplied by branches of the celiac trunk.

Venous Drainage: Blood drains into the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), which joins the portal vein.

Lymphatic Drainage

Lymph from the small intestine drains into mesenteric lymph nodes, which eventually empty into the cisterna chyli and then the thoracic duct.

Specialized lymphatic vessels called lacteals in the villi absorb dietary fats.

Nervous Supply

Sympathetic Innervation: Provided by the celiac plexus and superior mesenteric plexus, which regulate motility and blood flow. Parasympathetic Innervation: Supplied by the vagus nerve, which stimulates secretion and motility.

Peritoneal Relationships

The jejunum and ileum are entirely intraperitoneal and suspended by the mesentery, a double layer of peritoneum containing blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves.[1]

The duodenum is mostly retroperitoneal, except for its proximal portion.

Surface Modifications for Absorption

The small intestine has specialized structures to maximize nutrient absorption: Plicae Circulares: Circular folds of the mucosa and submucosa that increase surface area and slow the movement of chyme. Villi: Covered with absorptive enterocytes and goblet cells, villi further enhance the absorptive capacity. Microvilli: Form the brush border, containing enzymes for final digestion of nutrients.

Function

The small intestine is the primary organ for digestion and absorption of nutrients. Its structural adaptations, such as villi, microvilli, and a vast network of blood and lymphatic vessels, allow it to perform these functions with remarkable efficiency. Below is a detailed explanation of its functions:

Digestion of Food

The small intestine is the main site for the chemical breakdown of food: Carbohydrate Digestion: Enzymes like amylase (from the pancreas) and brush border enzymes (e.g., maltase, lactase, sucrase) break down polysaccharides into monosaccharides (e.g., glucose, fructose). Protein Digestion:

Pancreatic enzymes such as trypsin and chymotrypsin hydrolyze proteins into smaller peptides.[8]

Brush border enzymes (e.g., peptidases) further break these peptides into amino acids.

Fat Digestion: Bile salts emulsify fats into smaller droplets, allowing pancreatic lipase to break triglycerides into glycerol, free fatty acids, and monoglycerides. Nucleic Acid Digestion: Pancreatic nucleases (e.g., deoxyribonuclease, ribonuclease) digest DNA and RNA into nucleotides.

Absorption of Nutrients

The small intestine absorbs nutrients through specialized structures like villi and microvilli:

Carbohydrates:

Monosaccharides like glucose and galactose are absorbed via active transport using sodium-glucose co-transporters (SGLT-1).

Fructose is absorbed through facilitated diffusion.

Proteins:

Amino acids and small peptides are absorbed by active transport using sodium-dependent carriers.

Fats:

Fatty acids and monoglycerides are absorbed by diffusion into enterocytes, reassembled into triglycerides, and transported as chylomicrons via lacteals into the lymphatic system.

Vitamins:

Water-soluble vitamins (e.g., B-complex, C) are absorbed by diffusion or active transport.

Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) are absorbed along with fats.[7]

Vitamin B12 is absorbed in the ileum, requiring intrinsic factor from the stomach.

Minerals:

Iron is absorbed in the duodenum, regulated by hepcidin.

Calcium is absorbed in the duodenum and jejunum, facilitated by vitamin D.

Electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and chloride are absorbed throughout the small intestine.

Water:

Approximately 7-8 liters of water are absorbed daily by osmotic gradients.

Immune Defense

The small intestine plays a crucial role in immune surveillance:

Peyer’s Patches:

Found in the ileum, these lymphoid nodules detect and respond to pathogens.

Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT):

Scattered throughout the mucosa, GALT prevents the invasion of harmful microbes while promoting tolerance to beneficial bacteria.

Secretory IgA:

Produced by plasma cells, it binds to antigens and neutralizes pathogens in the intestinal lumen.

Motility

The small intestine ensures proper mixing and movement of food through various motor activities:

Segmentation:

Localized contractions mix chyme with digestive enzymes and bile, ensuring maximum contact with absorptive surfaces.[5]

Peristalsis:

Wave-like contractions propel chyme forward toward the large intestine.

Migrating Motor Complex (MMC):

Occurs during fasting, clearing undigested material and preventing bacterial overgrowth.

Secretion of Digestive Enzymes and Mucus

The small intestine secretes digestive enzymes from its crypts of Lieberkühn, including:

Brush border enzymes (e.g., maltase, lactase, sucrase, peptidases).

Goblet cells secrete mucus, which lubricates and protects the intestinal lining from acidic and mechanical damage.

Regulation of Digestive Processes

The small intestine plays a role in regulating digestion through hormonal secretion:

Cholecystokinin (CCK): Stimulates the release of bile from the gallbladder and pancreatic enzymes.[3]

Secretin: Stimulates bicarbonate secretion from the pancreas to neutralize acidic chyme.

Motilin: Initiates the migrating motor complex during fasting.

Water and Electrolyte Balance

The small intestine absorbs large quantities of water and electrolytes:

Sodium is absorbed actively via sodium-potassium ATPase pumps.

Water follows electrolytes through osmosis, maintaining hydration and fluid balance.

Microbial Interaction

The small intestine interacts with the gut microbiota, which contributes to:

The production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) via fermentation of undigested carbohydrates.

Synthesis of vitamins like vitamin K and certain B vitamins.

Preparation for Waste Elimination

By the time material leaves the ileum, most nutrients have been absorbed.

The remaining material, primarily fiber, water, and dead cells, is passed into the large intestine for further water absorption and eventual elimination.

Clinical Significance

The small intestine is critical for nutrient absorption and digestion, and its dysfunction can lead to significant clinical conditions:

Malabsorption Syndromes: Conditions like celiac disease and Crohn’s disease affect the small intestine’s ability to absorb nutrients, leading to deficiencies in vitamins, minerals, and proteins, causing weight loss, diarrhea, and fatigue.[2]

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): An overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine can cause bloating, diarrhea, and malabsorption.

Obstructions: Small bowel obstruction (caused by adhesions, hernias, or tumors) results in abdominal pain, vomiting, and requires immediate intervention.

Cancer: Though rare, small intestinal cancers like adenocarcinoma and lymphoma can occur.

Ischemia: Conditions like mesenteric ischemia (reduced blood flow) can damage the small intestine, leading to severe pain and life-threatening complications.

Published on December 31, 2024

Last updated on May 13, 2025

Last updated on May 13, 2025