S

Stomach

Organ for mechanical and chemical digestion of food

RegionAbdomen

SystemDigestive System

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the digestive system that functions as a reservoir for food. It is responsible for mechanically breaking down food and mixing it with gastric juices to form chyme, a semi-liquid substance. The stomach is divided into four main regions: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. It has a highly elastic structure, allowing it to expand to accommodate food and liquids.

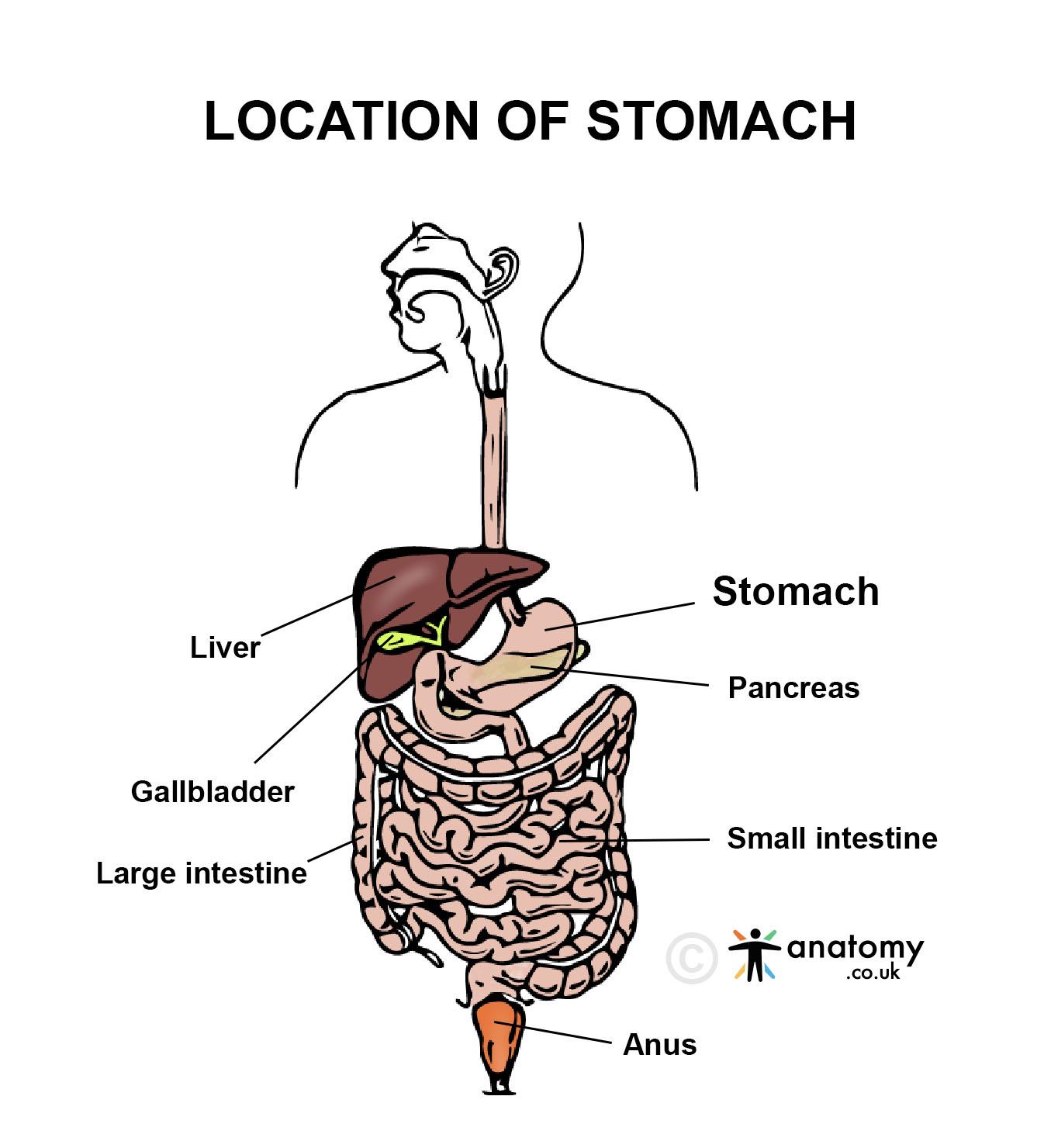

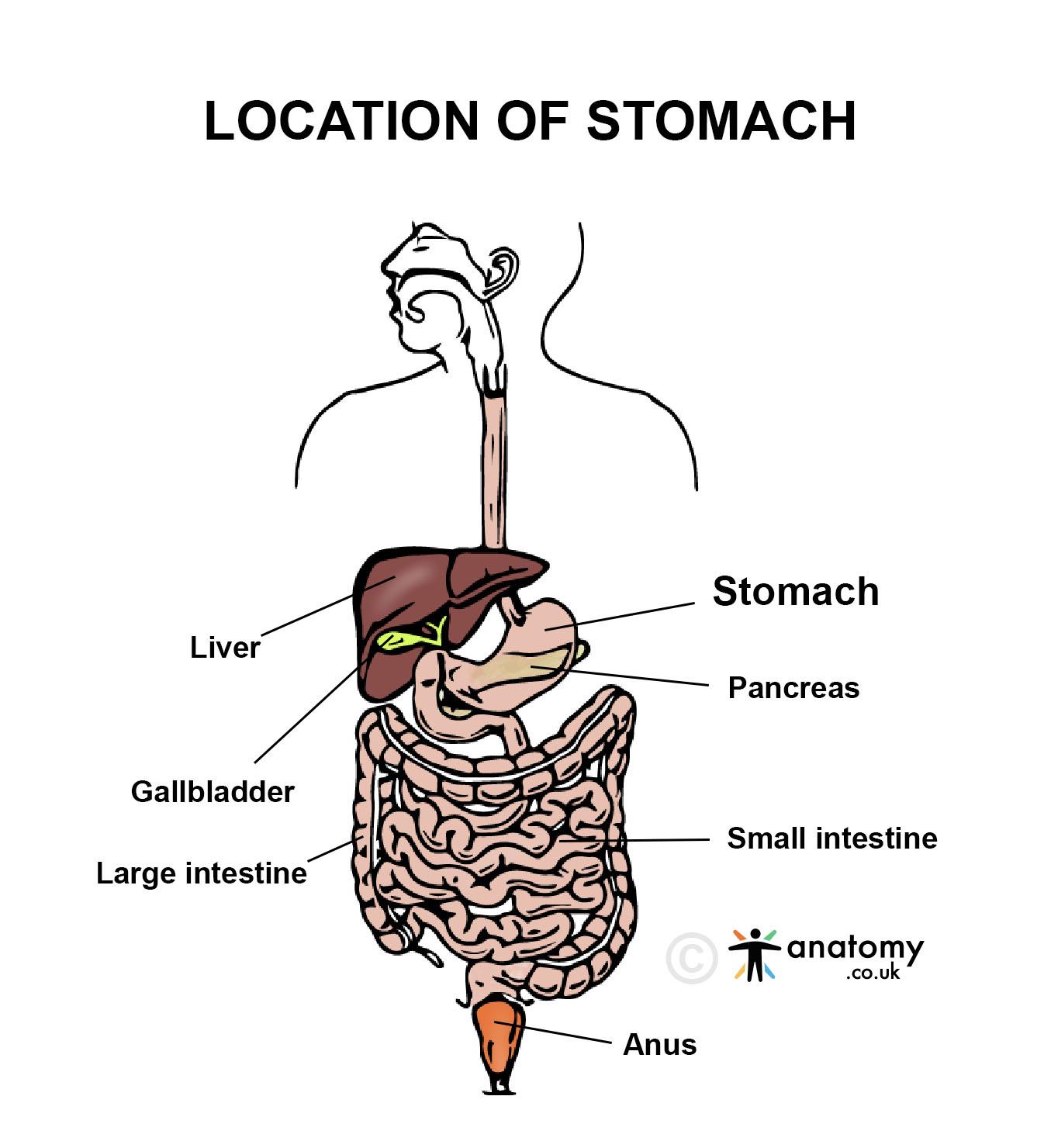

Location

The stomach is located in the upper abdomen, primarily in the left upper quadrant (LUQ).[1]It lies below the diaphragm and the heart, with its proximal end connected to the esophagus and its distal end to the duodenum of the small intestine.Anatomy

The stomach is a J-shaped, hollow organ in the digestive system designed for food storage, mechanical digestion, and chemical processing.[3] Below is a detailed description of its anatomy:Shape and Regions

The stomach is divided into four major regions, each with distinct anatomical features: Cardia:- The proximal part of the stomach, where the esophagus connects to the stomach via the cardiac orifice.

- Contains the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which prevents reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus.

- The dome-shaped portion above the cardiac region.

- Located under the diaphragm, it acts as a storage area for undigested food and trapped air.

- The largest region of the stomach, located between the fundus and pylorus.[4]

- Serves as the main area for mixing and digestion of food.

- The distal region of the stomach, divided into:

-

-

- Pyloric Antrum: Connects to the body of the stomach.

- Pyloric Canal: Leads to the pyloric sphincter, which regulates the passage of chyme into the duodenum.

-

Curvatures

Greater Curvature:- The longer, convex border of the stomach, running along the left side.

- Provides attachment for the greater omentum.

- The shorter, concave border along the right side.

- Provides attachment for the lesser omentum.

Wall Structure

The stomach wall consists of four layers, each with specialized features for its functions: Mucosa: Lined with simple columnar epithelium containing gastric pits that lead to gastric glands. Glands contain specialized cells:- Parietal Cells: Secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) and intrinsic factor.

- Chief Cells: Produce pepsinogen.

- Mucous Cells: Secrete mucus to protect the stomach lining.

- G Cells: Secrete gastrin, a hormone that stimulates acid production.

- Contains connective tissue, blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves.

- Houses the submucosal plexus (Meissner's plexus), which regulates glandular secretions.

- Inner Oblique Layer: Facilitates churning and mixing of food.

- Middle Circular Layer: Forms the pyloric sphincter.

- Outer Longitudinal Layer: Aids in peristaltic movement.

- Contains the myenteric plexus (Auerbach's plexus), which controls muscle contractions.[5]

- The outermost layer, formed by the visceral peritoneum.

- Provides structural support and reduces friction with surrounding organs.

Blood Supply

Arterial Supply: Supplied by branches of the celiac trunk, including:- Left Gastric Artery: Supplies the lesser curvature.

- Right Gastric Artery: Also supplies the lesser curvature.

- Right Gastroepiploic Artery and Left Gastroepiploic Artery: Supply the greater curvature.

- Short Gastric Arteries: Supply the fundus.

- Left and Right Gastric Veins.

- Right and Left Gastroepiploic Veins.

- Short Gastric Veins.

Lymphatic Drainage

Lymph from the stomach drains into gastric lymph nodes, gastroepiploic lymph nodes, and celiac lymph nodes.Nervous Supply

Sympathetic Innervation: Supplied by fibers from the celiac plexus, which regulate blood flow and inhibit gastric motility. Parasympathetic Innervation: Provided by the vagus nerve, which stimulates gastric motility and secretions.Anatomical Relations

Anteriorly: Related to the diaphragm, left lobe of the liver, and anterior abdominal wall. Posteriorly:- Related to the pancreas, spleen, left kidney, and adrenal gland.

- These structures form the stomach bed, separated from the stomach by the lesser sac.

Rugae (Gastric Folds)

The mucosa and submucosa form folds called rugae, which allow the stomach to expand significantly after food intake.Function

The stomach plays a vital role in digestion, serving as a reservoir for food, breaking it down mechanically and chemically, and regulating its passage into the small intestine. Below is a detailed explanation of its functions:Food Storage

- The stomach acts as a temporary reservoir for ingested food and liquids, allowing gradual release into the small intestine.

- The stomach’s rugae (folds in the mucosa and submucosa) allow it to expand significantly, accommodating volumes of up to 1-1.5 liters.

Mechanical Digestion

- The stomach’s muscular layers, particularly the inner oblique layer, facilitate churning and mixing of food.[6]

- These movements reduce food into smaller particles and mix it with gastric secretions to form chyme, a semi-liquid mixture.

Chemical Digestion

The stomach secretes various substances that break down food:- Hydrochloric Acid (HCl):

- Secreted by parietal cells, it lowers the stomach’s pH to 1.5-3.5, creating an acidic environment that:

- Denatures proteins, making them easier to digest.

- Activates pepsinogen into pepsin, an enzyme that digests proteins.

- Kills ingested pathogens.

- Secreted by parietal cells, it lowers the stomach’s pH to 1.5-3.5, creating an acidic environment that:

- Pepsin:

- Secreted as an inactive precursor (pepsinogen) by chief cells and activated by HCl.

- Breaks proteins into smaller peptides.

- Gastric Lipase:

- Produced by chief cells, it aids in the digestion of triglycerides into free fatty acids and monoglycerides.

- Intrinsic Factor:

- Secreted by parietal cells, it is essential for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine.

Secretion of Mucus

Mucous Cells in the gastric glands produce a thick, protective mucus layer:- Protects the stomach lining from corrosive gastric acid and digestive enzymes.

- Prevents auto-digestion of the stomach wall.[7]

Regulation of Gastric Emptying

The stomach controls the rate at which chyme enters the small intestine through the pyloric sphincter:- Gastric emptying is influenced by the nature of the chyme (e.g., fats delay emptying) and signals from the duodenum.

- Hormones such as cholecystokinin (CCK) and secretin regulate this process.

Hormonal Regulation

The stomach secretes hormones that coordinate digestive activity:- Gastrin:

- Produced by G cells in the pyloric antrum, gastrin stimulates:

- Secretion of HCl.

- Gastric motility.

- Growth of the gastric mucosa.

- Produced by G cells in the pyloric antrum, gastrin stimulates:

- Somatostatin:

- Inhibits gastric acid secretion when the stomach’s pH becomes too low.

Immune Defense

- The acidic environment of the stomach provides a defense mechanism by killing or inhibiting the growth of ingested pathogens.

- Gastric-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) within the mucosa contributes to the immune response.

Absorption

Although most absorption occurs in the small intestine, the stomach absorbs certain substances:- Water: Small quantities are absorbed, particularly when the stomach is empty.

- Alcohol: Rapidly absorbed through the stomach lining.

- Some Medications: Certain drugs, such as aspirin and NSAIDs, are absorbed in the stomach.

Regulation of Appetite

- The stomach produces ghrelin, a hormone that stimulates appetite.

- Ghrelin levels rise before meals and fall after eating, signaling hunger to the brain.

Clinical Significance

The stomach is a key organ in digestion and is involved in various clinical conditions:- Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD): Caused by excessive gastric acid secretion or Helicobacter pylori infection, leading to ulcers in the stomach lining and associated with pain, bleeding, or perforation.[8]

- Gastritis: Inflammation of the stomach lining due to infection, alcohol, NSAIDs, or autoimmune disorders.

- Gastric Cancer: Often asymptomatic in early stages, it can develop from chronic gastritis or H. pylori infection, presenting with weight loss, vomiting, and anemia.

- Gastroparesis: Delayed gastric emptying, commonly seen in diabetes, causing nausea, bloating, and vomiting.

- Hiatal Hernia and GERD: Displacement of the stomach into the thoracic cavity can lead to gastroesophageal reflux disease, with symptoms like heartburn and regurgitation.

Published on December 31, 2024

Last updated on May 17, 2025

Last updated on May 17, 2025